In many cultures, the beginning of winter is marked with a religious holiday dedicated to light. Northern Europeans have Saint Lucia, Hindus have Diwali, and Jews have Hanukkah, an eight-day festival in which candles are lit every evening to remember a miracle which blessed the rededication of the Beit HaMikdash (the Holy Temple) of Jerusalem, around the year 170 BCE. Although religiously it is not an official high holiday, Hanukkah is celebrated in one way or the other by most Israelis, both religious and secular.

The story tells us that once upon a time, the people of Israel had fallen under the domination of Greek emperors. Under foreign rule, many Jews had begun to act like Greeks, running around naked and abandoning Judaism. A small group of Jewish warriors launched a desperate rebellion, and after bitter fighting liberated Jerusalem. The Temple was rededicated, but only one flask of kosher olive oil was left to light the menorah, the traditional seven-branched chandelier, yet it burned miraculously for eight days until more kosher oil could be found.

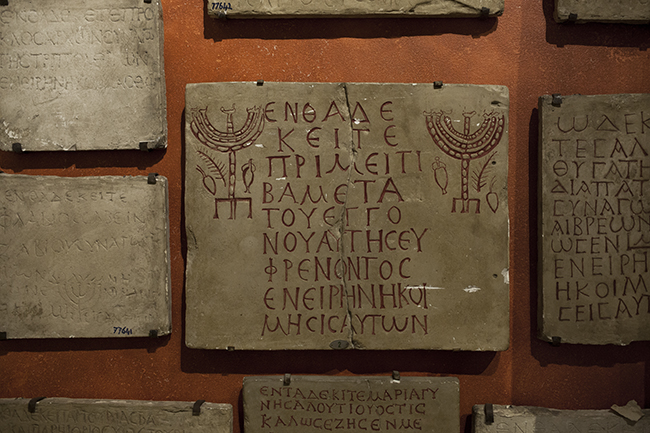

As witnessed by these ancient Jewish inscriptions found in Rome, just as those of today, the Jews of antiquity were influenced by the mainstream culture of the time. And in the hellenized Middle East of the Seleucid empire, the mainstream was Greece, with its history, its philosophy and its widely spoken language. Still today, some traditionalist Israelis refer disparagingly to their more secular or cosmopolitan fellow Jews, or more generally to leftists, as mityavanim, the hellenizers.

The central element of Hanukkah is the lighting of eight candles, one more for each night of the festival. While the exact ritual can be very different among Ashkenazim and Sephardim, or religious and secular Jews, generally speaking candles are lit and people sing some songs in Hebrew. Although the festival was traditionally meant to be held at home, with the candles visible from the outside in order to symbolize the triumph of light over darkness, today it is also practiced in public, especially in Israel.

In Jerusalem, religious Jews from the Chabad organization, which makes a point of making Jewish religious practices available to the masses, light a huge hanukkiya (the special nine-branched menorah used for the festival) in the central Kikar Zion (Zion Square). In modern times, the festival has been influenced by its proximity to Christmas, and the two holidays have become quite similar, especially in America, where it has become traditional to give presents to children, who would otherwise be left of out of the winter capitalist fest.

The major of Jerusalem Nir Barkat (center) joins the Chabad rabbis for their Hanukkah celebration. Politicians make sure to take part in as many candle-lighting celebrations as possible, a necessary job in Israel’s diverse society.

The member of Knesset (the Israeli parliament) Aryeh Eldad, choose to mark Hanukkah by lighting the candles at a electoral rally against African migrants in Tel Aviv’s Gan Levinsky (Levinsky Park). Campaigning as defenders of Jewish purity against foreign influences, the leaders of the right-wing party Ozma LeYisrael (Strenght to Israel) described the event as symbolical of their struggle as children of light against the children of darkness, presumably referring the dark-sinned African asylum seekers.

Residents of southern Tel Aviv shout xenophobic slogans, calling for the cleansing of their neighbourhood from the kushim (the ancient word for black-skinned Africans, now practically a racist insult) The vehement reaction of some conservative sectors of Israeli society to outside influences, such as the influx of some 50,000 African refugees, is often painted by the political right as a continuation of the struggle of

Over the centuries, some rabbis have emphasized the miracle of the candle lasting for eight days to downplay the military aspect of the original story. The intervention of divine providence was stressed in order to prevent Jews from getting too many ideas from the ancient Hebrews’ armed revolts against foreign empires, which ultimately ended with total defeat, the destruction of the Second Temple and the dispersion of the Jewish people.

Others mark the festival by making sufganyot, deep-fried jelly doughnuts which are one of Hanukkah‘s main features. In a reference to the miraculous oil lamp, the general tradition is to eat lots of foods fried in oil, which is also a necessary component of the candles that are lit every night.

Whether as a cautionary tale or a celebration of Jewish resistance to foreign oppression, as a replacement for Christian holidays or a call to political action, the story of Hanukkah and its play of light and darkness remains about one of the central elements of the history of the Jewish people – its fascinating and at times complicated relationship with the Other.