Sud Est:

Jewish Refugees in Salento, 1944-1947

On the beach of Santa Maria al Bagno, August 1946. (From the collection of Paolo Pisacane)

Southern Italy, 2017

70 years have passed, but Antonio Sanapo still thinks of the two old Jewish ladies who lived next to his family’s house when he was a child. “Paprika, paprika”, he remembers them saying while pointing at the red peppers grown by his father, “they would always came round and give us cans of peanut butter in exchange for our peppers. They were really fond of red peppers.”

We are in Tricase, a small village in Salento on the south-eastern tip of Puglia, and the two old ladies Antonio is talking about were Jewish refugees staying at DP (Displaced Persons) Camp 39. As the Second World War finally neared its end, millions of refugees were on the move all across Europe, looking for a new home. Laying right in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, the southern Italian region of Puglia was a busy junction along many of those journeys.

Salento had always been a land of passage between east and west, and it was here that Titus’ ships returned to after his legions laid waste to Jerusalem and destroyed the second Temple, bringing thousands of Jewish captives with them. Upon disembarking, some were ransomed by locals Jews who wanted to spare them the humiliation of being paraded in chains through the streets of Rome, and we can imagine them staring longingly across the Mediterranean sea, towards the land they had been exiled from.

Almost two-thousand years later, other Jews would come to those same shores, about to embark on the opposite journey: between 1944 and 1947, thousands of Jewish refugees were housed in DP camps in Salento, and the memory of their extraordinary encounter with the local communities still reverberates today. “In the end they all went to Palestine, and some to America”, Antonio says wistfully, “but I still remember them. I will never forget the time when the Jews lived with us.”

Less than 80 km separate Santa Cesarea Terme, where DP Camp 36 was, from the other side of the Adriatic Sea. Looking carefully, one can see mountains towering above the horizon.

To get a glimpse of that time, a good place to start is the Museum of Memory and Hospitality of Santa Maria al Bagno, built to exhibit a triptych of wall paintings left by one of the refugees who stayed in the village’s DP Camp 34. In one of the paintings, the Jews of the Galut break through barbed wire to gather in South Italy, from where they march to the Land of Israel. There are old photos on the walls, showing scenes from the beach, women with babies and groups of smiling people. At the centre of the room, a table displays an accordion and a wedding dress, as if they have been chosen to symbolise the entire experience.

The museum is the brainchild of Paolo Pisacane, a local historian who arranged for the wall paintings to be restored and collected a beautiful collection of photographs from the time. He is currently working on a book of testimonies and stories about the refugees, and has spent much of his life to preserve the memory of their passage through the villages of Salento. As with many people in the four villages, this is his story too: around the time of his birth, his mother Anna Pisacane was very close to a refugees girl, who helped her take care of the newborn child. Paolo eventually met that Jewish girl many years later, in Jerusalem, “and she told me that she felt more attached to our village than to her birthplace. There the Jews had been betrayed, she said, and sometimes she felt as if she was re-born in Santa Maria al Bagno.”

During the war, Puglia had largely been spared from the fighting, and the advancing English and American armies turned it logistic hub for their invasion of Italy, seizing many properties along the coastline to use as rest areas for their officers. To reduce frictions with the locals, the new authorities confiscated mostly empty holiday homes, and there were plenty of those in Santa Maria al Bagno, Santa Maria di Leuca, Tricase and Santa Cesarea Terme, four small sea resorts that mostly consisted of summer villas scattered among the house of the few permanent residents.

As the frontlines moved further north, the villas where then used to house the masses of displaced people flocking to the liberated areas, which included growing numbers of surviving Jews who made their way to Italy in the hope of sailing to Palestine. By 1944, DP camps had been established in each of the villages, but instead of being kept in a separated area as is usually the case, these refugees found themselves living right in the middle of the surrounding communities, and became part of their daily lives.

One of the refugees in a picture she left to someone in Santa Maria al Bagno. (From the collection of Paolo Pisacane)

Like Antonio Sanapo and nearly everybody in this story who is still around, Paolo Iacobelli was a teenager at the time, studying at Tricase’s elementary school. “One morning the headmaster came in to tell us that we were getting a new classmate, and then he brought in this beautiful, blue-eyed girl. Her name was Geltrude Krauss.” She was part of a group of refugees that had arrived on a boat from Albania and spoke some Italian, but at first nobody understood what had brought her to Tricase, although it didn’t seem to matter. “We just sat there and stared at her, hypnotised by how different she looked. We didn’t know she was Jewish or what that meant, and anyway back then one just didn’t go and talk to a girl. So we tried to impress her from a distance.”

They all came from very different worlds: Geltrude had grown up in Vienna, while her new classmates were mostly the children of farmers and fishermen. Many of the Jewish refugees originally came from the great cities of central and eastern Europe, and must have seemed rather highly educated to the inhabitants of four small villages in one of the poorest regions of Italy, which was barely emerging from twenty years of Fascism. “Everybody was totally enamoured with Geltrude, but she was going out with some older guy, and was totally out of our league. She was also the best student our school ever had,” Paolo Iacobelli continued, “although one day I managed to solve a math problem that even Geltrude hand’t been able to understand. That was probably my proudest day at school.”

Other times it did not go so well at first. In one of the testimonies collected by Paolo Pisacane, Enrico Schirosi recalled the day on which his family found out their summer house had been occupied by strangers. They tried to approach the newcomers, but were violently chased away. “In the following days, we began hanging out with the new inhabitants of our house, and we got to know them. One of the older refugees had eaten an entire prickly pear fruit without peeling it, and you can imagine the consequences. My mother had to use her pliers to pluck all the thorns from the poor fellow.”

As it often happens, it was food that brought such diverse people together at first. After years of war and rations, the people in the villages were starving. The Jews on the other hand were under the care of UNRRA, the UN agency tasked with assisting refugees at the time, which supplied them with bread, canned food and blankets. Aside from food and shelter, the newcomers needed practically everything, and before soon they started trading what they had for fresh vegetables, clothes, wine and much more. Legend has it that they first thing they looked for in Tricase was an accordion to play some music, and were given one in exchange for some white bread.

The ‘Porta d’Oriente‘ (Gate of the Orient) café in Santa Cesarea Terme still shows the Hebrew signs left by the refugees, who used it as a canteen during their stay in the village.

Donato Schirinzi, born in 1927 in Santa Maria di Leuca, remembers the efforts of the refugees of DP Camp 34 to improve their food situation: “the American soldiers had already established a kitchen, with an old Italian guy making pasta all the time. But the Jews wanted to cook their own stuff, so they asked for raw food and set up their own canteens. The food there was a bit salty.” In fact, over the following years the refugees often ended up feeding the locals, especially during the winter months, when they shared whatever they had with the hungry locals. “In Tricase they saved us all from starvation, I tell you”, Antonio Sanapo explained me, “some were against the refugees and some were more in favour, but we all benefited from it. After all, many of them had just been liberated from concentration camps, and they knew what hunger was.”

There are plenty of stories about food, like that time some fishermen in Santa Maria al Bagno caught an enormous sea turtle, and their families threw a party to celebrate the event. Some of the refugees pointed out that kashrut forbade them from eating a turtle, but refusing an invitation for food in South Italy has never been easy, and in the end they joined the feast, an act whose significance was not lost on the locals. Listening to the countless stories about refugees gorging on polpette (meatballs) and locals coming to terms with exotic dishes, it appears as if shared meals were definitely not an exception. Donato Schirinzi’s mother, for example, often had dinner at the house of a neighbouring Jewish couple from Poland, two doctors she had befriended after giving them some wool socks. “Their children had died and they were completely alone, so she tried to visit them every evening.”

As the exchanges between the two communities intensified, any initial diffidence was quickly overcome, although one wonders how did people exactly speak to each other. Vittorio Perrone, who was a teenager in Santa Maria al Bagno, jokes that “at first we used our hands, and every small thing took forever to explain. But we were young, and we picked up things fast. I learned my English playing poker with some of the Jewish boys.”

Very few among the refugees spoke any Italian, but everybody tried their best to get by. “There was this Rumanian girl who had come to use my mother’s sewing machine”, Rita Basile told me in Tricase, “she kept saying she wanted her dress ‘shorted‘, and my mother really couldn’t understand what she wanted. Nobody wore such short dresses at the time.”

Just like with food, there are plenty of stories about another one of life’s basic needs, clothing, with quite a few involving the ‘modern’ dress choices of the refugees. At the time, women wearing trousers were simply unheard of in South Italy, and the sight of Jewish girls hanging around in shorts undoubtedly provided further incentive to try and make small talk, no matter the language barriers. On his part, Paolo Iacobelli taught himself “a few sentences in German from a dictionary I found, like ‘wie gets‘ (how’s it going), but I was never brave enough to use them.”

The blankets provided by UNRRA, whose high-quality fabric made them a highly coveted commodity, also played an important role. Paolo Pisacane’s mother, for example, met the refugee girl after being asked to make a jacked out of one of those blankets. “It had UNRRA written on it, and however I tried to cut it, you could still see the letters. So I decided to leave the entire word across the back, like one of today’s brands, and she loved it.”

Rita Basile shows a UNRRA blanket she was given by a refugee.

Shortly after that, the girl’s parents sent her to Anna Pisacane to learn how to make clothes, and over time several professional schools were established in the villages, where local artisans and fishermen shared their skills with the refugees.

At the conference of the Organisation of Jewish Refugees in Italy, held in Rome at the end of 1945, the refugees had demanded that the network of Jewish and Zionist groups assisting them focus not only on their material needs, but also on providing education and cultural activities in the DP camps. Almost a third of the organisation’s budget was devoted to this endeavour which saw to the establishment of schools, theatres and several Yiddish newspapers, all while operating in a foreign land right after a world war. In the villages of Salento, the locals were absolutely impressed by the degree of organisation within the DP camps, and tried to get involved as much as possible.

Vittorio Perrone had befriended a group refugees while being treated in the camp’s hospital, and therefore had access to the camp’s two communal villas, kibbutz Aliyah and kibbutz Ba’derekh. “They kept themselves busy all the time, you could really see they wanted to start a new life. There was a drama school with a big stage where they were always rehearsing shows, and dance classes too. They taught themselves Hebrew, Italian and English, and there was also a lot of music, sometimes with the American soldiers. That’s where we discovered jazz and the boogie-woogie. I also learned that Russian song, Oci Ciornie.”

In the best Zionist tradition, great emphasis was also placed on sports, and many locals have fond memories of groups of young Jews running around their village, singing songs and doing gymnastics on the beach. Antonio Sanapo saw them so many times that he learned the songs by heart, and can still sing them today.

A group of Jewish volunteers and locals seen in Villa Filograna in Santa Maria al Bagno, which was used as a canteen and a recreational centre. (From the collection of Paolo Pisacane)

Another thing people remember are the parties. Rita Basile explained that “the refugees had a bar in one of the villas by the harbour, and there was a lot of dancing going on there. I used to go quite often with my sisters, and I remember this old couple who were always dancing together, every evening.” Many of the Jewish refugees were young, Rita continued, “and we were young too, so we met, like young people do.”

The English and American soldiers were also young, and the occupying authorities often held parties in some of the villages’ most beautiful villas, where the military headquarters were located. Vittorio remembers one of those parties especially well. “They even sent a military truck around, to collect people, it was a beautiful friday night.” Around midnight, an English officer told the band to stop playing and grasped the microphone, telling the Italian guests that they had to leave the party immediately. “We were getting all the girls, so they wanted us out. We had to leave, but then saw that the Jews were leaving too, in solidarity. The soldiers got the message, and let all of us back in.”

Listening to the stories and looking at the pictures, it is easy to imagine the time as a bit of a summer-camp, and everybody points out that it was only a matter of time before fixed couples appeared and people began getting married. Hundreds of weddings were celebrated in the DP camps of Salento, and local women often offered their wedding dresses to the young brides. Everybody was obviously invited, and many people I met have been to at least one Jewish wedding, including Antonio Sanapo. ”There was a guy with a small hat, he was the one actually doing the marriage, under some strange umbrella they had. Then they all started dancing in circles, shouting and singing. They danced the whole night!”

A few weddings between refugees and locals also took place, although those were somewhat less celebrated. A young Italian girl in Santa Maria al Bagno actually run away from her home to marry her Jewish fiancee Zvi Miller, who painted the graffiti in the museum, and eventually converted to Judaism and sailed with him to Israel. In Tricase, a young lawyer married a girl from Bucharest, but the other refugees did not take their mixed relationship too well and the newlywed couple had to move out of the village for a while. She returned after the camp was closed, and has been living there ever since.

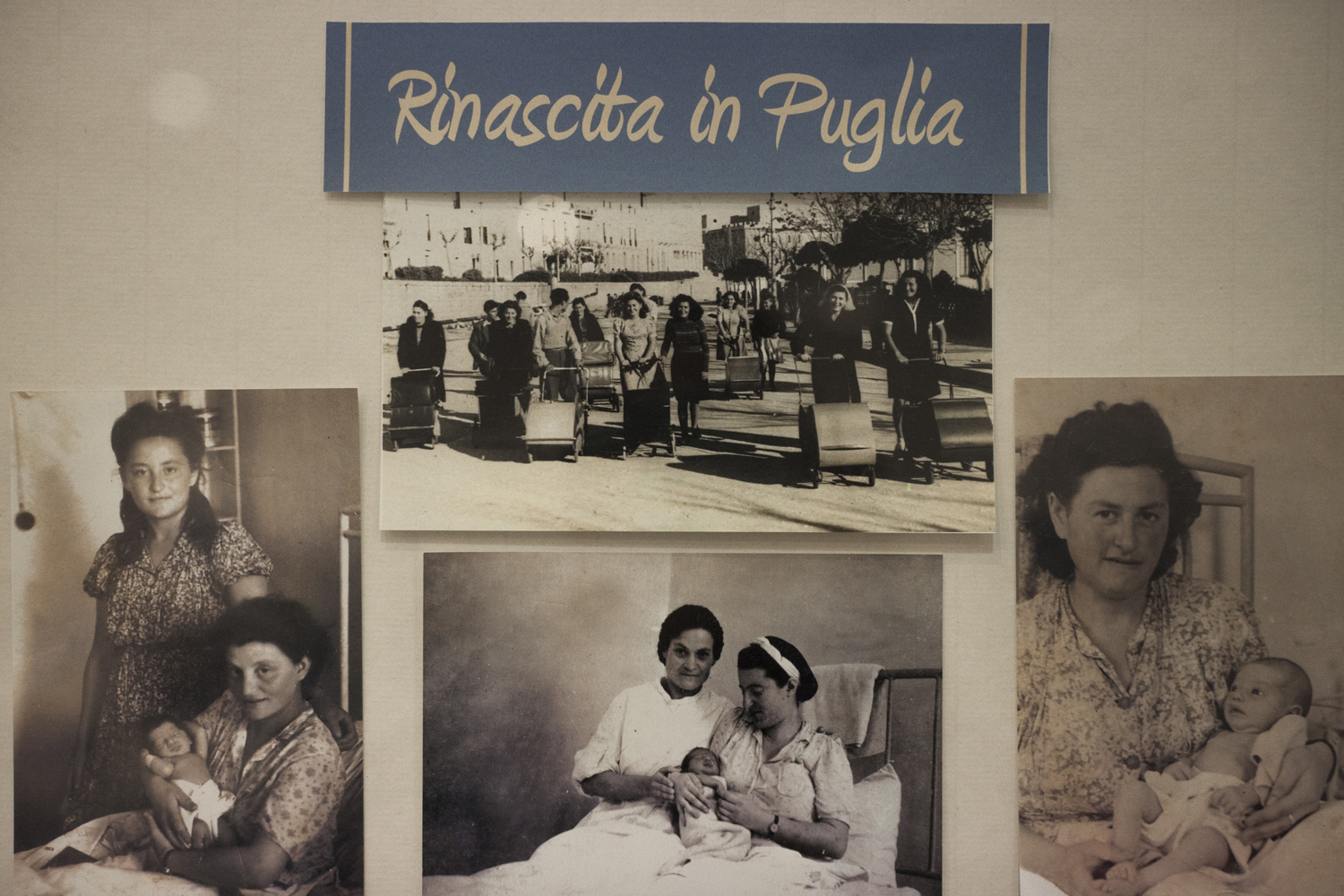

Rebirth in Puglia: photos on display in the museum of Santa Maria al Bagno.

One can easily imagine what happened next. To thank Paolo Pisacane’s mother for the jacket, the girl’s father built her a wooden baby carriage, and “after that the girl would come to our house every day and take Paolo out for a walk. It was very convenient for her, otherwise she couldn’t hang out with the other Jewish girls, whom in the meantime all had children.”

More than two hundred children were born in the camps, and Antonio still smiles when he remembers “the Jewish girls walking around the village, pushing their babies and looking so happy. They had told us what German soldiers had done to them.” The sight of Jewish girls pushing baby carriages was perhaps one of the strongest symbols of the rebirth experienced by the refugees, many of whom were just emerging from the horrors of the Holocaust. There were no Jewish communities in Salento before the war, and Italian state propaganda had kept largely silent about what was being done to the Jews, therefore most people in the villages did not know what the refugees had gone through, although some like Antonio had immediately noticed something was amiss. “When they arrived, sometimes it was a grandmother with a child, sometimes a lone widow, sometimes orphans who had lost their entire family. Then they started telling us what happened.”

One person who did know from the beginning was Elena Iannace, Paolo Iacobelli’s school teacher, who wrote a note in the class journal on the day Geltrude arrived. “The students have warmly welcomed their new classmate, and promised to not hurt her feelings. On the other hand, my job has became a bit harder, especially when it comes to history. But I shall not alter the truth of the facts because of her, for to do so would give my students a distorted idea of what really happened in the history of our country.”

The truth of the facts was that the Fascist regime actually participated in the Holocaust, but anti-semitism had not really taken hold in Italy, and the refugees encountered no hostility and there were no incidents serious enough to be still remembered today, with the exception of one episode in Tricase. “On that Sunday we had an agreement”, Paolo Iacobelli explained, “we were going to borrow their army truck to go play an official match, and they could have our football pitch for the day. But then for some reason they said we couldn’t get the truck, and that they wanted to play on our pitch anyway.” Tempers ran high, and then somebody among the refugee shouted that since the Italians had lost the war, they should just shut up and go away. Things escalated quickly, stones were thrown and the refugees found themselves surrounded by an angry mob. They ran away towards the harbour, and in their anger broke a few windows on the way, enraging the locals even further.

After that, relationship were a bit frosty for a few days. “There was a bit of a cold war, they kept a low profile and stayed away from the centre of the village, but about a week later we got an invitation for a reconciliation dinner in one of the villas. ” The refugees cooked a lot of food, an orchestra from the village played music “and we made peace. Things went back to normal the next day.”

Zvi Miller’s wall paintings at the museum of Santa Maria al Bagno.

The growing numbers of Jewish refugees, many of whom remained unregistered in order to elude the English authorities on the way to Palestine, and the extensive modifications carried out on the villas to accommodate them did cause some resentment among the locals. In May 1946 a demonstration was announced: “We are not responsible for what they claim to have suffered in the German concentration camps”, the posters read, before demanding the immediate return of the villas of Santa Maria al Bagno to their owners. Although it did cause some panic among the refugees, who set up barricades to defend themselves and asked their local friends to hide their families, the demonstration was called off after only about five people showed up.

Certain local officials known for their Fascist sympathies also denounced the extensive black market activities of the refugees, which must have been quite significant considering that people in the villages still refer to the act of shopping at a market as ‘going to the Jews’, and tried to use the news of the fight in Tricase to demand the closure of the DP camps, arguing that the local communities saw them as “traffickers, loan sharks, profiteers and the main cause of all hardships” and demanding that they be moved somewhere else, possibly to a closed camp.

In the words of Ercole Morciano, a local historian from Tricase, “every attempt to divide the two communities failed miserably,” and the fight remained an isolated episode. “The relationships were too strong. People met every day, they shared everything and they knew each other personally.” It is worth noting that just a couple of weeks after the incident, the municipality of Tricase awarded honorary citizenship to several people from the DP camp including an Austrian doctor, Friederich Mayer, who had treated hundreds of locals for free and had brought penicillin to the village for the first time.

By the spring of 1947, the camps were being gradually closed as the refugees continued their journey, which often was a clandestine and possibly dangerous one, since Jewish emigration to Palestine was still illegal and there were persistent rumours about boats of Jews being sunk by the British. Many locals remember being afraid that something bad would happen to their friends while they crossed the sea, in a depressing anticipation of what other people must be experiencing today on other shores of the Mediterranean sea. Sometimes there was time for a goodbye dinner, but more often than not the departure was kept secret so as not to alert the English. “One day you were at the beach with them,” Vittorio concluded, “and the next day they were gone.” Geltrude simply stopped coming to school, and the villas were once again empty. “I was sixteen when the refugees arrived,” Donato Schirinzi told me at the end of our interview, “and in a sense we became adults together. I moved to Rome shortly after they left, there was nothing to do here.”

Local actors from Tricase pose in their stage costumes for a play on the Jewish refugees.

After decades of relative oblivion, the recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in this story among the people of Salento. Thanks to the efforts of local historians such as Paolo Pisacane and Ercole Morciano and the establishment of the museum, the memory of the Jewish refugees has spread far beyond those who have met them personally, and became part of the collective memory of the four villages. In Santa Maria al Bagno one square is even named after Golda Meir, whom according to an unfounded rumour spent a lot of time in the village’s DP Camp. Local schools and authorities have also embraced this memory, and cherish it as a proud symbol of Salento’s tradition of hospitality to others, a tradition that remains very much alive. “We try to apply the model of our grandfathers to the current migration emergency, which is actually no longer an emergency”, Nardò’s major Giuseppe Mellone told me, “hundreds of migrant workers come here to work every year, so we set up places where they can live with dignity. This has always been a land of passage, it’s part of our history and it’s still true today.”

In Tricase, a local theatre company produced a play based on the stories of the refugees and of their interactions with the people of the village. “It was a bit hard not to compare what happened then with the way we think of refugees today”, the play’s author Walter Del Prete told me, “and not to wonder as to why the two are so different.” While on one hand the fact that the Jewish refugees were never supposed to stay in Salento undeniably played a role, the answer probably lies in the way it happened, and in how that way of dealing with people in need shaped the way they were perceived by the local communities, as opposed to today’s specialised assistance that sets refugees and migrants apart from society and depicts them as passive victims we have to take care of, often allegedly at the expense of our own poor.

Living side by side and sharing their everyday life, the refugees and the residents of these four villages could see each other as people and formed bonds that continue to this very day. From time to time, some of the refugees and their descendants come back to visit, and on one such occasion a group of Israeli women who were born in the DP camps symbolically returned a wedding dress and accordion, which are now on display in the museum of Santa Maria al Bagno and serve as a fitting symbol for the time when the Jewish refugees lived with the people of four villages of Salento.